This post is the fifth in a series-in-progress by company president Megan St. Marie about heirlooms and objects related to her family history that she keeps in her office to inform and inspire her work at Modern Memoirs.

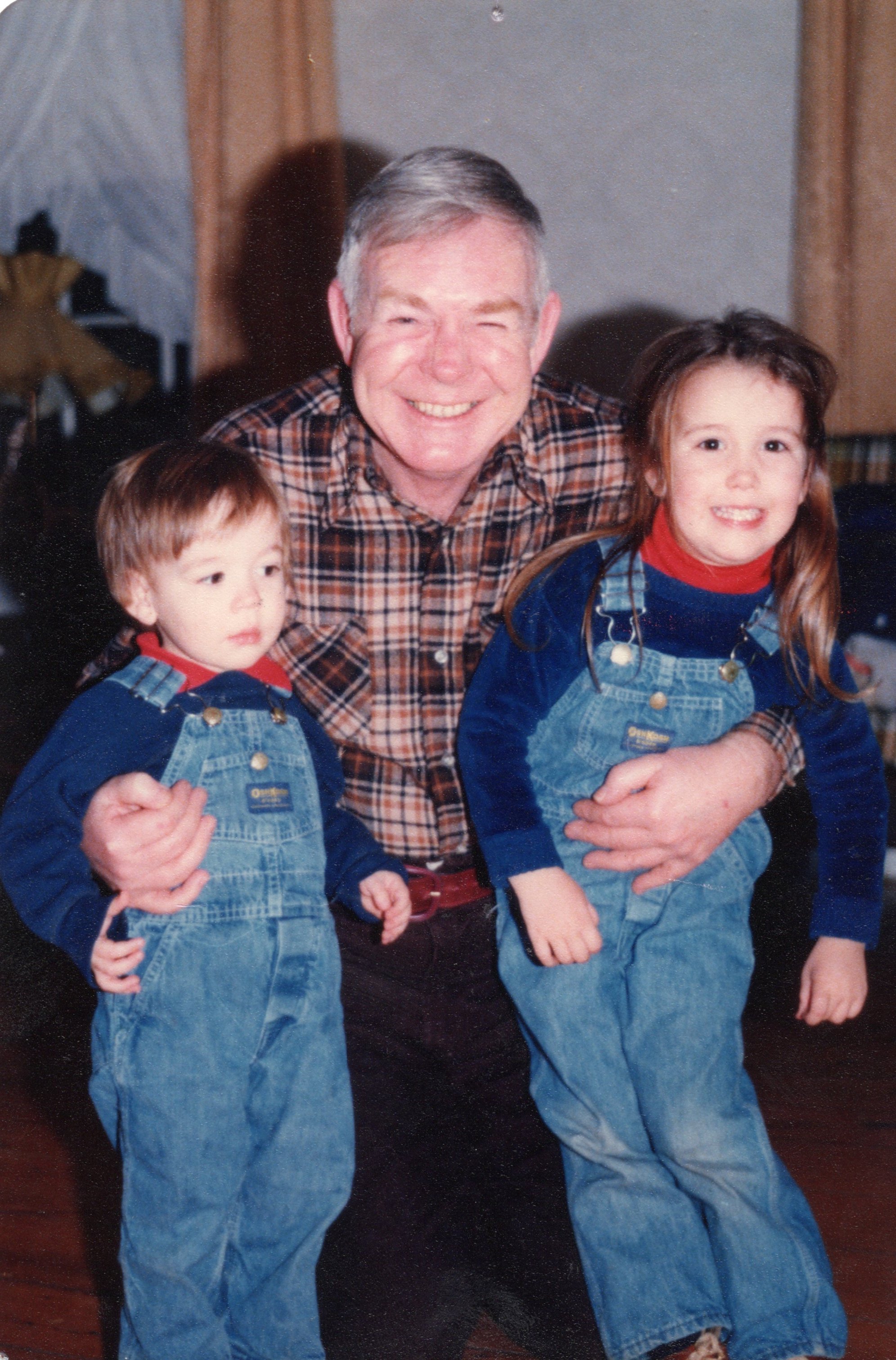

The Henri and Maria Laroche family in 1941, ten years after Henri’s release from prison on bootlegging charges. (Front row, L–R) Laurent (seated), Leonidas, Henri, RoseAnna, Maria, Marie-Ange, and Leonard. (Back row, L–R) Clement, Gertrude, Therese, Florence, Lucienne, Yvonne, Alice, and Jean-Marie

Megan St. Marie’s baby quilt hanging in her Modern Memoirs office, made by her paternal grandmother Lucienne Marie Laroche Lambert

Several quilts decorate my office at Modern Memoirs, all passed down from different family members and restored by my aunt Rita Lambert Lavallee. One is a pink quilt made by my paternal grandmother, Lucienne Marie Laroche (1912‒1986), which hangs on the back of my office door. It was a gift for me at my birth, the firstborn child of her firstborn, my dad, Raymond A. Lambert. For many years this quilt covered my childhood bed, and at some point it was marred by ink stains leaked from a pen I carelessly laid down, likely after scribbling away on some homework assignment. When Aunt Rita mended the quilt as a wedding gift to me, she used new fabric to repair the frayed edges, but she couldn’t totally remove the stains. As I sat down to write this piece about my baby quilt, not quite sure what I wanted to say, noticing the presence of these small blots of ink led me through a chain of associations going all the way back to a Prohibition-era family secret.

First, the recollection of sitting on my bed with this quilt while doing my homework made me remember that the grandmother who made it for me never completed her schooling. Like my father and me, she was the eldest child in her family. She loved school and did well in her classes, but difficult circumstances befell the family when her father, Henri Edouard Laroche (1893‒1966), was arrested for bootlegging—or being a “rum-runner”—during the latter years of the Prohibition era. She left school for good at that point to help her mother, Maria Gagne Laroche (1898‒1976), care for their farm and for her younger siblings, a decision my father has said was a heartbreak for her.

Close-up of ink stains on Megan St. Marie’s baby quilt

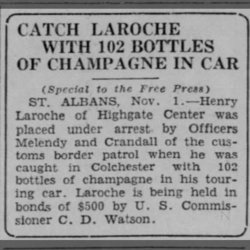

There was no other choice. By that point, Henri and Maria had nine surviving children, including my grandmother, and Maria was pregnant with their tenth. It’s not difficult to surmise that the responsibility of providing for their large brood prompted my great-grandfather to risk smuggling 102 bottles of champagne from his native Québec across the border into Vermont in November 1929. That autumn when he was planning the run had been calamitous for the American economy, after all, with the stock market finally crashing in October. I can imagine that tensions and anxieties were high, even in the small, quiet border town in the northwestern corner of Vermont where the Laroches made their living on a dairy farm.

Newspaper clipping from the Burlington Free Press, documenting the arrest of Henri Laroche

Newspaper clipping documenting the sentencing of Henri Laroche for transporting liquor, 1929

Law officials apprehended Henri just south of Winooski, Vermont on November 1, 1929. They confiscated the champagne from the trunk of his car, and later that month he was sentenced to a year and a day in the federal prison near Atlanta, Georgia, over a thousand miles away. The sentence must have been quite an ordeal for my great-grandfather. For one thing, French was his first language, and he spoke little English. I’m also sure he worried terribly about his family in Vermont, and it must’ve been a sadness to miss the birth of his new son, Clement, in 1930. On a lighter note, while the fiddle was a mainstay of the soirées or kitchen parties he and his Franco American community regularly enjoyed, Henri reportedly returned home from Georgia with a deep distaste for banjo music, which he had heard every day during his incarceration.

Henri and Maria’s children knew about their father’s prison term, but shame made them keep it a secret from their own offspring for many years. The French word for shame is “honte,” which to my anglophone ear sounds an awful lot like “haunt.” Indeed, shame can exert a spectral presence across generations, haunting people with a painful compulsion to maintain silence, and inhibiting healing. My father never learned of the story until one of his aunts blurted it out in an unrestrained moment at a family reunion, years after Henri had died.

I don’t see my great-grandfather’s imprisonment as a stain on the family, like ink spilled on the fabric of the baby quilt his daughter would go on to make for me. If there’s any shame in the story today, I think it belongs to the disastrous prohibition experiment, which ultimately came to an end in 1933 with the ratification of the 21st Amendment, just a few years after my great-grandfather completed his sentence. A review in the online journal Seven Days about a book from an oral history project in Vermont offers the following commentary, which might as well be about Henri Laroche:

John Rainville, in his account of his family’s French-Canadian agricultural heritage, manages to touch on this subject as well. As a bystander, his recollections of the rum-runners tend to be more objective. He mentions that some local men were caught and sent to federal prison in Atlanta. “These guys, you know, they were poor,” he says. “They were trying to make a dollar…it’s almost like drugs today.”[1]

I’d go a step further than Mr. Rainville to say it’s exactly “like drugs today” in terms of how the draconian War on Drugs has led to a crisis of mass incarceration in the United States, with some 2 million people jailed and imprisoned, a 500% increase in the past 40 years. (See The Sentencing Project’s data[2] for more information on this sad reality of our nation and its disproportionate impact on BIPOC populations.) The tragedy doesn’t stop with those who are imprisoned, but ripples out into families and communities.

That ripple effect was apparent in the 1920s in Henri Laroche’s family. I wonder, for example, how my grandmother’s life might have been enriched and changed for the better by continuing her schooling. Such speculation may seem fruitless in its inability to change the past, and if my great-grandfather hadn’t been arrested, and my grandmother had continued her schooling, I would not exist. History had to happen just as it did for my father, and then me, to come into being.

Put another way, everything is connected, with lives stitched together by choices and chance like the threads that bind the pieces of a quilt. Rediscovering this simple, profound truth time and again is one of the great rewards of family history work. I didn’t know I was going to write about her father’s imprisonment when I decided to write about the quilt my grandmother made for me when I was born. Reflecting on my writing process in real time brings to mind lines from Natalie Babbitt’s Tuck Everlasting,[3] a favorite book I read as a child (perhaps while sitting on that same ink-stained quilt): “No connection, you would agree. But things can come together in strange ways.”

I’ll add wondrous to that phrase—family history work can help us see connections between people and stories and themes in strange and wondrous ways. That seeing, in turn, can prompt empathy, healing, and maybe even the dissolution of the specter of shame. To paraphrase neuroscientist Daniela Scholler,[4] the stories we tell about the past aren’t about the past; they are about how we perceive the past in our present moment. It follows that if we can change our perception, we can change our lives, and maybe the lives of our ancestors, too.

[1] Quoted in Cathy Resmer’s review of Bootleggers, Brothels and Border Patrols: Conversations with Vermonters, Volume 7, a project of the Vermont Folklife Center, December 19, 2001. See the full review at Bootleggers, Brothels and Border Patrols: Conversations with Vermonters, Volume 7 | Books | Seven Days | Vermont's Independent Voice (sevendaysvt.com)

[2] Criminal Justice Facts, https://www.sentencingproject.org/criminal-justice-facts/

[3] Babbitt, Natalie. Tuck Everlasting. Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 1975.

[4] Specter, Michael. “Partial Recall: Can Neuroscience Helps Us Rewrite Our Most Traumatic Memories?” The New Yorker, May 12, 2014. https://www.newyorker.com/magazine/2014/05/19/partial-recall