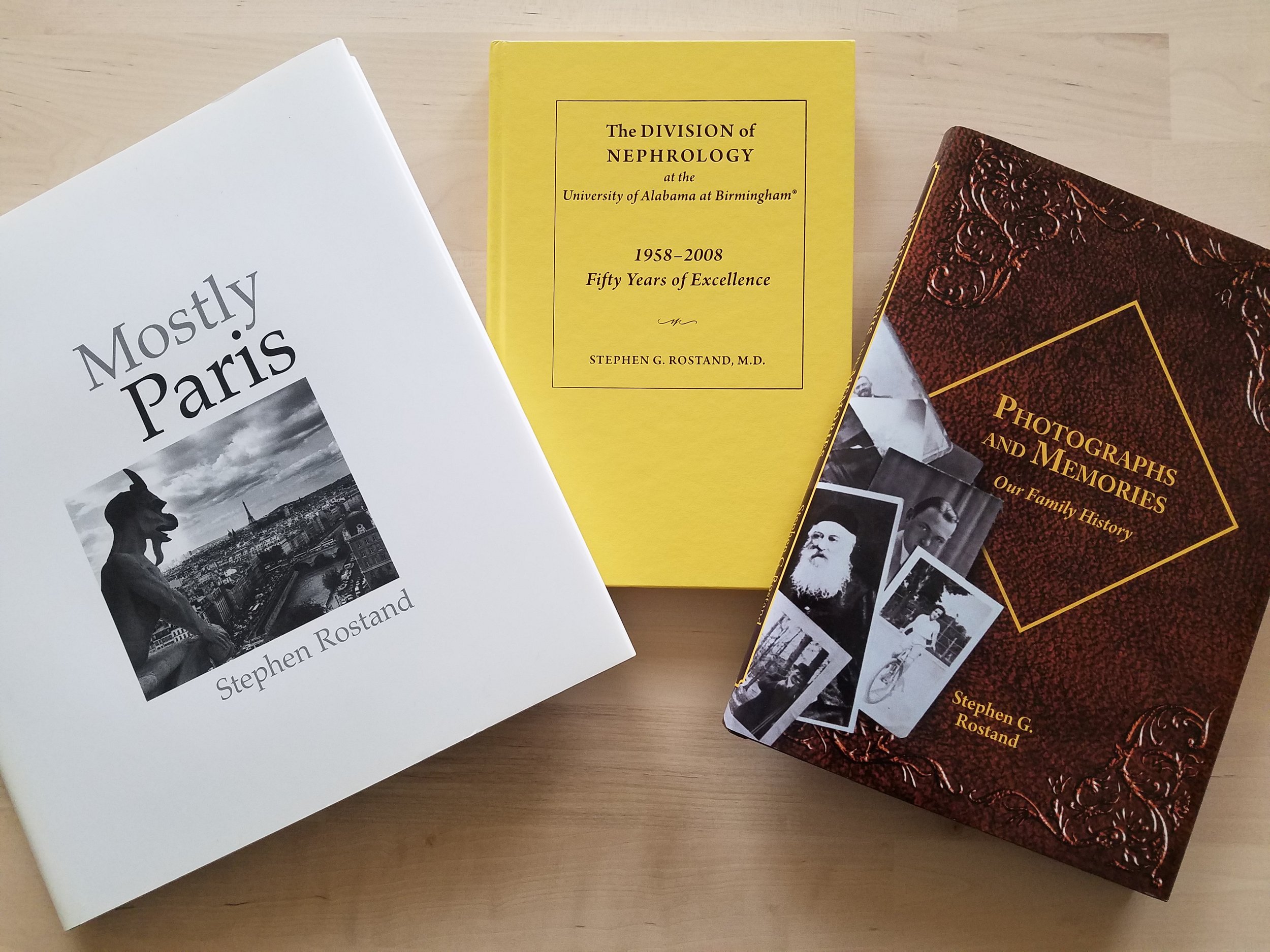

Dr. Stephen Rostand is a repeat client with Modern Memoirs. His photography book entitled Mostly Paris was his first project, and it came out in 2007. The second book, a department history entitled The Division of Nephrology at the University of Alabama at Birmingham, 1958–2008, Fifty Years of Excellence, was published in 2014 and reprinted in 2019. The third book, a family history book entitled Photographs and Memories: Our Family History, was published in 2020.

We asked the author to reflect on what the publication process was like for him for these three very different books, and what it has meant to share them with others.

1. While you are an M.D. by profession, your hobby/passion is photography. What prompted you to have a sampling of original 8x10 glossy prints transformed into a book? Do you have a favorite photo or two in this collection?

Stephen Rostand: I have been actively photographing for at least 50 years. During that time, I have accumulated thousands of photographs and have reduced the number to those that I think are exceptional. At one point I started considering what to do with them and how to preserve them for family and friends who seemed to like them. I had been to many photo exhibitions and had also seen the works of well-known photographers in books. I felt that many of my photographs were as good as theirs, and that gave me the idea for a book in which I could preserve the best of them. However, because I am a private person, I had to overcome my initial reluctance to expose my inner self to others. After all, what is the photograph but a projection of the photographer, his/her vision, viewpoint, and attitude towards the subject? The photographer is the photograph and vice-versa. It took me about a year to further winnow the photographs, select or write commentary to accompany those photographs, and find someone to produce the book. I was fortunate to find Modern Memoirs through their small ad in The New Yorker. They produced a magnificent book that is, in itself, a work of art. I have distributed the books as gifts to family and friends in the United States and Europe. It’s hard to answer which photo is my favorite because, truthfully, all of them are. Each one represents something different, and I cannot select one over another. It’s like asking who your favorite child is.

2. Your department history is shared with students, colleagues, and residents of the Division of Nephrology at the University of Alabama at Birmingham. What sort of feedback have you received from your book’s readers? How does providing them with this institutional knowledge enhance their studies and their practice?

Stephen Rostand: When I retired after nearly 40 years on the faculty, my director asked me if I would write a history of our division. I had been one of the original members of the division and had participated in its growth and subsequent importance. Having majored in history in college and having read many historical works, I was flattered and eager to do it. More than a chronology or collection of anecdotes, I decided to write a historical narrative that spanned 50 years, from the beginning of our division to the arrival of the chief who asked me to write the story. I used the university archives, interviewed past and present colleagues, discussed some of the university politics affecting our division, and dealt with some very sensitive issues involving people who were still on the faculty. It took nearly three years to research and writing. To say the least, it was very well received and has been distributed to all our past trainees, the dean, university president, visiting faculty, and each trainee at the time of their graduation. It also serves a public relations function for our division. Although the book is not meant to help our graduates in their medical practice, many of our graduates are bench researchers. It describes the evolution of our field, the growth and development of our division, its faculty, and how the division was managed through a variety of difficult problems and gained its national prominence. It is instructive about how to grow a successful group and it should give our graduates a sense of pride for having been associated with the program.

3. Your third book, Photographs and Memories, is a lovely blend of genealogy, historical context, and personal story. It includes genealogy charts, many photographs, and an appendix of “legendary” anecdotes. What did you learn about gathering a family’s history into one book, and what advice do you have for others who may be considering a similar project?

Stephen Rostand: Writing a family history requires time, attention to detail, persistence, objectivity, tact, understanding of what kind of history you wish to write, and what its goal is. Will it be an attempt to find and catalog every member of your immediate and distant family? Or will it be a more personal, intimate look at who and what kind of people your first-degree relatives were? You will need to determine if there are any existing documents and photographs of past and present family. If there are living parents and grandparents, try to interview them. Include aunts, uncles, cousins, brothers, sisters, and anyone who knew them well. Draw on your own memories as well. Also remember that your childhood impressions of your parents, grandparents, and other family members may well be different from your opinions as an adult. Thus, make sure that what you write is objective or else you may create friction and enemies in the family. If necessary, you may need to get help with your genealogical research.

4. After previously completing two very different books, why did you add this third book to the collection? Why was it important to you that you record your family history?

Stephen Rostand: As I wrote in the preface to my family history, “Our worst fear may not be death but rather the loss of memory. Life is short, memory fleeting, and the nuclear family temporary and centrifugal. Over time we disperse.” After several generations we become strangers. I wanted to make sure my children and grandchildren and cousins knew something about their origins so they would not be orphans in history. After all, our past is part of all of us and knowing who we are should help guide us in the future. As I am nearing the end of my life, I thought this history would be an important gift to pass on. I was fortunate to have all the notes my father took when he interviewed his family when he was a young man and to have various documents and the family photo album that contains photos going back to 1898. Because these important items are not in the best condition, I felt they should be preserved. It was for these reasons that I wrote the family history.

5. How did the writing process itself help you reflect upon or uncover insights into the people and events you wrote about?

Stephen Rostand: In writing the family history I was able to reassess my parents’, grandparents’, aunts’, and uncles’ lives by placing them in historical context and seeing their growth and development through photographs. It gave me an adult perspective of my forbears, an opportunity, for the first time, to understand the complex relationships between our families, and to understand myself and my relationships better. It also brought me in contact with more distant family members whose history I could only touch on peripherally and superficially. These relatives provided me with additional details of our genealogical tree and sent me the personal memoirs of at least one family member whose experiences living in Europe from 1910 until 1949 were fascinating. Unfortunately, it arrived in my hands well after my history was published. Thus, a written family history is part of a continuum and is never really completed. Mine was written in the hope that one of my children would continue the story.