This post is the second in a series-in-progress by company president Megan St. Marie about heirlooms and objects related to her family history that she keeps in her office to inform and inspire her work at Modern Memoirs.

An 1893 edition of Henry Wadsworth Longfellow’s Evangeline: A Tale of Acadie on display in Megan St. Marie’s office at Modern Memoirs

While I trace most of my ancestry to Québec, I also descend from French-speaking people called the Acadians. During the 17th and 18th centuries, they emigrated from France and settled in what are now known as the Canadian Maritime Provinces—Prince Edward Island, Nova Scotia, and New Brunswick—as well as in northern Maine. Known as “the neutral French,” the Acadians refused allegiance to France and England as those European nations struggled for dominance over the strategically positioned Maritimes during the French and Indian War (the North American phase of the Seven Years War battled in Europe). The Acadians also formed strong alliances with the Indigenous Mi’kmaq nation, alliances fortified by a high rate of intermarriage and by what historian John Mack Faragher calls a “spirit of mutual accommodation,” in his book A Great and Noble Scheme: The Tragic Story of the Expulsion of the French Acadians from Their American Homeland.[i]

Faragher’s subtitle references the forcible removal of the Acadians from their homeland during Le Grand Dérangement (the Great Expulsion) as a strategic element of the British war effort. Between 1755 and 1765, roughly 80% of the Acadian population was rounded up, detained in camps, and shipped off to the British colonies, Québec, France, and England. A small portion of those exiled managed to resettle and maintain their francophone culture in present-day Louisiana, where they became knowns as Cajuns, but most died or were widely dispersed and acculturated in what Faragher and other historians regard as a tragic incidence of ethnic cleansing. Families were torn apart, thousands perished, and because of the outright devastation of Acadian villages, high rates of illiteracy, and bias in British colonial record-keeping, this history was long suppressed.

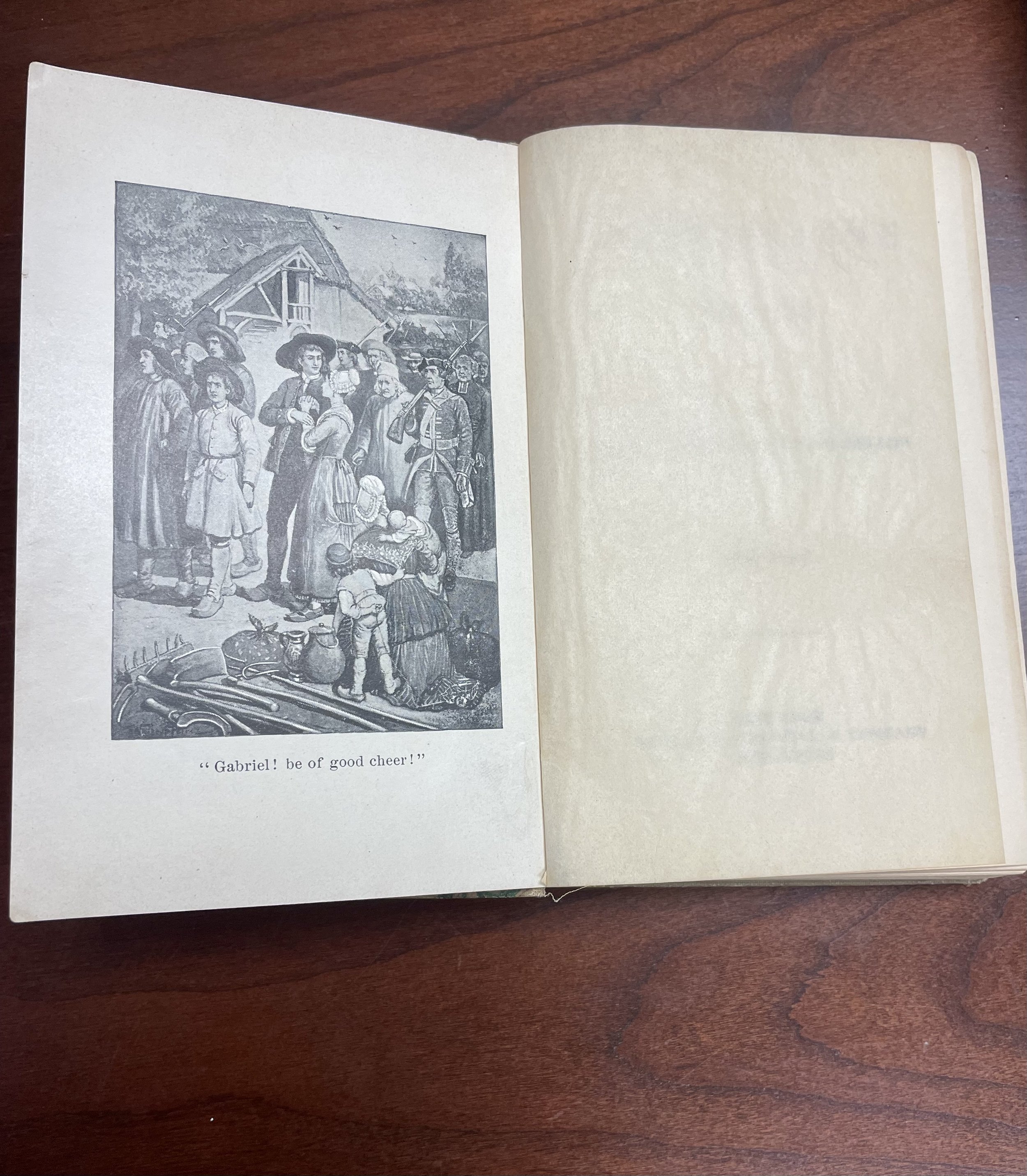

Megan St. Marie’s 1893 copy of Longfellow’s Evangeline: A Tale of Acadie, open to the frontispiece illustration (with facing vellum overlay) depicting the fictional Acadians Evangeline and Gabriel before they are separated during Le Grand Dérangement

Henry Wadsworth Longfellow’s epic poem, Evangeline: A Tale of Acadie,[ii] was written roughly a century after Le Grand Dérangement and tells the story of a fictional young Acadian woman, Evangeline Bellefontaine, who is separated from her fiancé, Gabriel Lajeunesse, when the British expel them from Grand Pré (in present-day Nova Scotia). I have an old copy of this book on display in my office at Modern Memoirs, given to me by my father-in-law, Terry St. Marie, who shares my Franco-American heritage. It’s a beautiful, small 1893 edition, with a cover made to look like birchbark (perhaps evoking the poem’s opening lines, “This is the forest primeval”) and a frontispiece showing Evangeline and Gabriel before their separation. It stands both as a tribute to this part of my heritage and as an inspirational piece of bookmaking.

While Evangeline’s publication revived interest in Acadian history and culture in 19th-century Canada and the United States, my reading of Faragher illuminated how the poem erroneously romanticizes colonial America as a place of sanctuary for the Acadians. In truth, they were unwelcomed throughout the colonies, with anti-Catholic and anti-French sentiment leading colonial governors and the general citizenry to persecute, reject, and fail them. Death by exposure, disease, and starvation was widespread, as scores of Acadians were forced to camp out in the bitter cold on the Boston Common, others were repelled from ports of entry, and children were separated from their parents and sent to live with British colonial families as laborers.

A quick review of my own paternal genealogical record shows well over a dozen Acadian ancestors directly caught up in Le Grand Dérangement, including:

· An eight-times great-grandfather Jean Baptiste Bernard, who was born in New Brunswick, expelled in the early years of Le Grand Dérangement, and died in Québec in 1757, just two years after the start of the expulsion.

· An eight-times great-grandmother Madeleine Boudreau, who was born in Acadie, expelled in Le Grand Dérangement, and died in Connecticut in 1768, just three years after the end of the expulsion.

· A seven-times great-grandmother Marie Comeau, who was born in 1708 in Acadie, expelled during Le Grand Dérangement, and died in France in 1779. Her husband, Joseph Honoré Landry, also died in France in 1764, so it appears they were not separated. Their son, Simon Landry, was born in 1740 in Acadie, and he was separated from his parents. He married a Marie Rose Cyr (born in 1745 in Acadie) and they were expelled to Québec, where they died in the early 19th century.

Close-up of Green Gables counted cross-stich made by Megan St. Marie, which now hangs in her Modern Memoirs office

Reading Faragher’s book and connecting it to my genealogical record made that remote history feel closer. It also forced a reckoning with not just Evangeline’s romanticization of history, but with the anti-French sentiment in another beloved book set in the Maritimes, L.M. Montgomery’s Anne of Green Gables. Anne captured my heart as a child because I saw myself reflected in and validated by her loquacious, ambitious, sentimental, sensitive, bookish self. It wasn’t until I was an adult teaching the novel in courses at Simmons University that I recognized how her story marginalizes and disparages the francophone population of Prince Edward Island (PEI), descendants of those very Acadians who actually brought me into being. In his essay “L.M. Montgomery and the French,”[iii] Gavin White quotes Montgomery and writes,

“There's never anybody to be had but those stupid, half-grown little French boys; and as soon as you do get one broke into your ways and taught something he's up and off to the lobster canneries or the States,” (AGG 7). On this sentence hangs the whole story of Anne of Green Gables, for Marilla and Matthew Cuthbert would not have sent for an orphan from Nova Scotia had hired help been reliable. But it was not reliable, it was French. And French meant half-grown and little, for the remaining French of Prince Edward Island had been pushed off their lands and into the bush when the colony was ceded to Britain in 1763, and they had not eaten well since. And French meant stupid, for the English-speakers of the Island only saw the French as servants, and they thought of them as the politically dominant races have all too often thought of dominated races.

White’s essay highlights other instances in the text that cast PEI’s francophone population as stupid and inferior, and I can’t argue with his critique. Instead, I argue with the novel itself, weighing my love for all it has given me against feelings of disloyalty to the ancestors who gave me my very existence.

Anne of Green Gables suncatcher created by artist Olive Barber, Catch the Sun Designs, a Christmas 2020 gift to Megan St. Marie from her husband, Sean St. Marie, that hangs in her Modern Memoirs office window

Several years ago, I traveled to the Maritimes with my husband, Sean, and we visited various sites that memorialize Le Grand Dérangement and preserve Acadian culture and history. We also visited the Green Gables Heritage Place, where I bought an embroidery kit of Green Gables. The finished piece now hangs on the wall of my Modern Memoirs office. A suncatcher Sean later gifted me shows Anne skipping past Green Gables and hangs in the window opposite that wall. Both pieces connect me to this cherished book of my childhood, while they also serve as useful inspiration for me to engage clients with work that challenges them to examine the stories they tell about their lives and their family history from many angles. After all, sometimes we are so close to a text we love—whether it’s one we’ve read or one we’ve written—that we can’t see “the forest primeval” for the trees; and just as reading new texts can shed light on those we’ve read in the past (as Faragher’s book and White’s essay prompted my new reflections on Evangeline and Anne), good editing can help writers see their own work in new ways, prompting revisions to make it stronger, accessible to more readers, and truer to their intent.

In a rather stunning bit of coincidence, I carry out my editorial work with clients in a town named for Lord Jeffery Amherst, the army commander who captured Canada for Great Britain during the very war that prompted the persecution and expulsion of my Acadian ancestors. I am because they were, and this reminder of the inescapability of history affords me a small feeling of triumph as I lay claim to my Acadian heritage and draw inspiration from it in my work.

[i] Faragher, John M. A Great and Noble Scheme: The Tragic Story of the Expulsion of the French Acadians from Their American Homeland. WW Norton & Co., 2005.

[ii] Longfellow, Henry Wadsworth. Evangeline: A Tale of Acadie. Notes by Nathan Haskell Dole. Thomas Y. Crowell & Company Publishers, 1893.

[iii] White, Gavin. “L. M. Montgomery And The French”. Canadian Children's Literature/Littérature Canadienne pour la Jeunesse 78.21 (1995): 65–68.