This post is the fourth in a series-in-progress by company president Megan St. Marie about heirlooms and objects related to her family history that she keeps in her office to inform and inspire her work at Modern Memoirs.

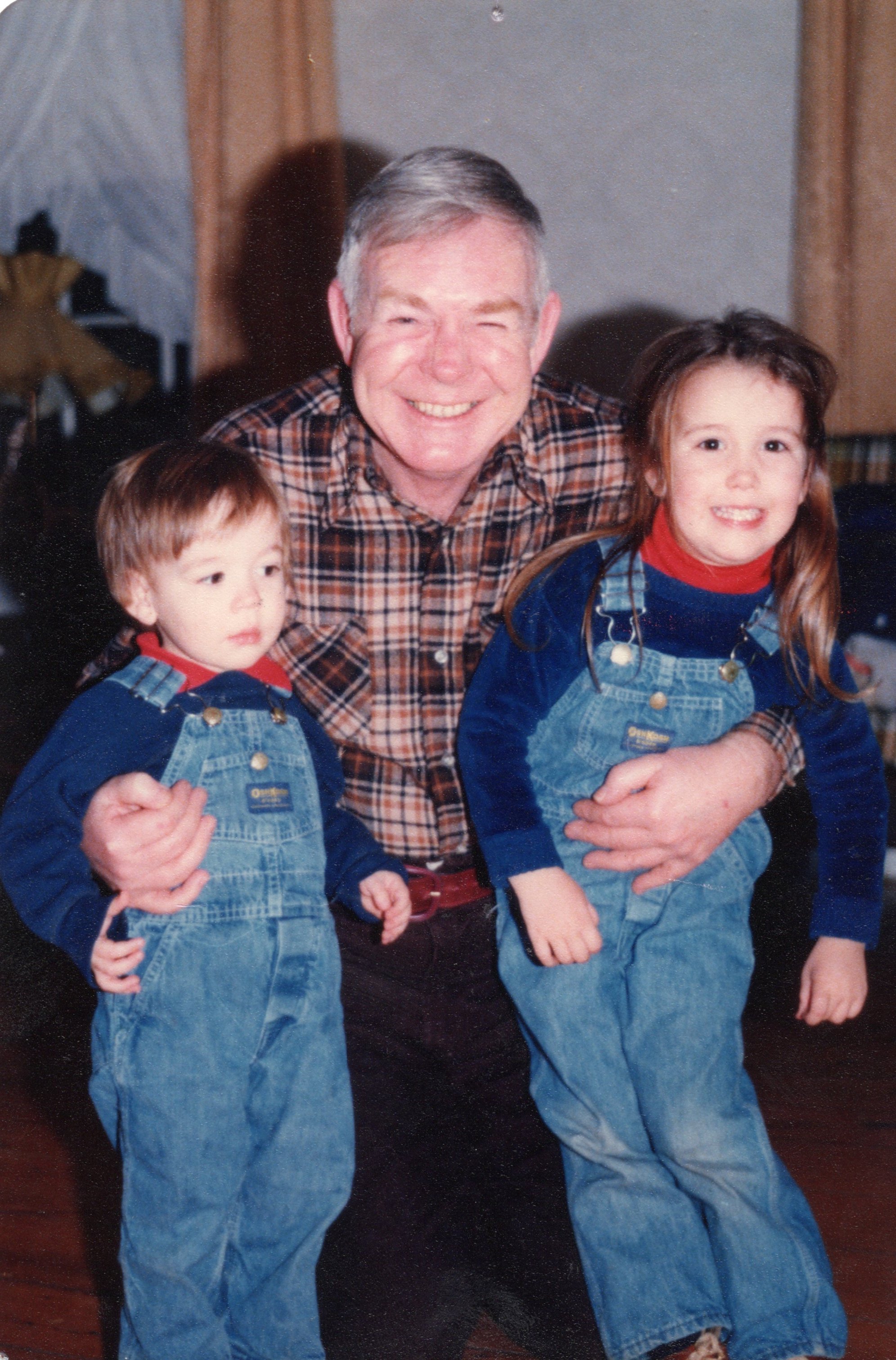

Megan St. Marie as a child (at right) with her brother, Sean Paul Lambert (at left), and their maternal grandfather, Paul Edward Dowd, 1980

As an undergraduate at Smith College, I took a fascinating course on African religions. Nearly thirty years later, in my work at Modern Memoirs, I often recall a reading assignment from John Mbiti’s African Religions and Philosophy[1] that introduced the Swahili terms “Sasa” and “Zamani.” These words describe concepts of time that hold deep relevance for work on family history and genealogy.

Loosely defined, Sasa refers to the present, or to those memories held by people who are alive today. Sasa is forever receding into the deep past of Zamani, or that which predates any living memory. With regard to ancestors, those people who are deceased but still recalled by the living exist in the realm of Sasa. In other words, although they are dead, they remain in the (remembered) world of the living. Then, when the last person who holds a living memory of a deceased person also dies, the ancestor moves into the realm of Zamani.

The notion that the dead we remember are not fully lost to the past but exist in current (Sasa) memory holds potential solace for the living. Thinking of people I love who have died as existing in Sasa transcends mere sentimentality or nostalgia to awaken feelings of both comfort and the sacred in me. Comfort arises because the losses seem somehow eased, and the sacred because of a sense of responsibility to remember.

As he neared the end of his life, my maternal grandfather (whom I called Papa) said to my mother, “I just don’t want to be forgotten.” Born to an Irish immigrant mother and her Irish American husband in Boston nearly 100 years ago, it’s safe to say that my grandfather, Paul Edward Dowd (1925‒2014), was unfamiliar with the Swahili terms and concepts of Sasa and Zamani. Though he was an avid reader, he never went to college to study African religions or any other subject—something he once told me he regretted. But even if he didn’t use the word “Sasa,” my grandfather’s desire to be remembered evokes his awareness of different planes of existence in the present. By stating what he did not want after his death (to be forgotten and thus relegated to the past in which he lived), he asked for what he did want (to be remembered in the present after his death).

And so, I remember my Papa. I remember times we spent together. I remember the particularities of personality and presence that made him the man he was. I remember stories he told me about his life.

Prints depicting Boston landmarks displayed in Megan St. Marie’s Modern Memoirs office

I’ve written before about how heirlooms and objects related to family history can help spark such memories, but although I’ve filled my Modern Memoirs office with many such items and have others at home, most are from my father’s side of the family. I do, however, own a set of prints depicting famous landmarks in Boston that sits atop my office bookshelves in honor of my Papa. He didn’t give me the prints (they were a gift from my father-in-law), but because he was born and raised in Boston, I associate those street scenes with him. These were places he grew up knowing—Faneuil Hall and Quincy Market, the Boston Common, the gold-domed State House and the Old State House, Boylston Street, Copley Square, Louisburg Square, and the Old T-Wharf.

Close-up of a print depicting the Old T-Wharf in Boston

USS ARD-17, the ARD-12-class floating drydock on which Megan St. Marie’s grandfather Paul Edward Dowd served during WWII

Paul Edward Dowd (front row, center) stationed with other Navy servicemen in the Pacific during WWII, cir. 1945

Though he didn’t work at the Old T-Wharf, this waterfront scene brings to mind how my grandfather did work in the Boston shipyards as a young man. This experience led him to join the Navy at the age of 19, and he served in the Pacific Theater during WWII aboard USS ARD-17, an ARD-12-class floating drydock. On November 30, 1944, ARD-17 was damaged by a near miss from a Japanese bomber while anchored at Kossol Roads, Palau. I believe this was the incident my grandfather told our family about when he found himself near one of the ship’s guns on the deck during an attack. As a shipfitter, he hadn’t been trained to use that weaponry and it was unmanned. Another higher-ranking sailor saw him in the chaos of the attack and shouted, “Shoot it, Paul! Shoot it!”

“I didn’t know what the hell to do,” Papa would say when telling this story. “So I just held onto the thing without ever firing it, and I yelled ‘BANG! BANG! BANG! BANG! BANG!’”

Though he always laughed when telling this story, he admitted to being scared. The first time I heard him tell it, I remember feeling something akin to fright when I realized that if the attack had gone differently, killing my Papa at age 19, he never would’ve come home from the war, and I would not exist.

A maple syrup jar from Megan St. Marie’s maternal grandparents’ 60th anniversary party

But he did come home. After the war, my Papa returned to Boston and married my grandmother in 1950. They raised seven children together and celebrated their 64th wedding anniversary before his death in 2014. I sadly missed their 60th anniversary celebration, but I have a glass maple syrup jar they gave out as a party favor in honor of the decades they spent living in my home state of Vermont. The syrup is long gone, but the empty jar remains in my office as a memento of the life they built together as part of what Tom Brokaw famously called “The Greatest Generation.”[2]

Today, my grandparents and many others of their era exist only in living memory, or Sasa. The National World War II Museum notes:

Every day, memories of World War II—its sights and sounds, its terrors and triumphs—disappear. Yielding to the inalterable process of aging, the men and women who fought and won the great conflict are now in their 90s or older. They are dying quickly—according to US Department of Veterans Affairs statistics, 240,329 of the 16 million Americans who served in World War II are alive in 2021.[3]

This museum is working to make sure that the memories of WWII do not disappear entirely, and on a smaller scale, I think we do the same kind of work at Modern Memoirs. My grandfather’s service is well-documented in public records, but his personal stories exist only in the memories of those of us who heard him tell them. Like the harrowing but humorous story I relate above, most of his stories were funny. He was not a fan of “mushy stuff,” and it suffices to say that my sentimental streak is not something I inherited from him, though I did get so much more. That truth is what compels me to write about my Papa today, and many Modern Memoirs clients come to us for similar reasons. They, too, feel the comfort and responsibility of loving their relatives and ancestors in the Sasa realm and wish to preserve their memory in writing. As Sasa gives way to Zamani, the books we help our clients create can serve as individual museums, curating and preserving the stories, voices, and individuality of those who came before us for generations to come.

[1] Mbiti, John S. African Religions and Philosophy. Oxford: Heinemann, 1990.

[2] Brokaw, Tom. The Greatest Generation. New York: Random House, Paw Prints (imprint of Baker & Taylor Books), 2010.

[3] https://www.nationalww2museum.org/war/wwii-veteran-statistics