This post is the sixth in a series-in-progress by company president Megan St. Marie about heirlooms and objects related to her family history that she keeps in her office to inform and inspire her work at Modern Memoirs.

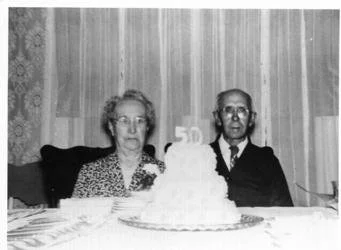

Megan St. Marie’s great-grandparents Anastasie “Tazzy” Delia Raymond Lambert and Alfred “Fred” Damian Lambert celebrate their 50th wedding anniversary, 1955

I recently wrote an editorial letter to a client, encouraging him to say more about his wife in his memoir. The two met as teenagers and have been together for over 50 years. It seems clear from his narrative that he adores her and that she has played a big role in supporting him in his success as a businessman. Even though his memoir is mainly focused on his career, that sense of adoration made me very curious about the woman he married. I want to know more about her, and I’m guessing that she’d be moved by what her husband has to say about her. However, this client may choose not to add more detail about his wife’s life and their marriage, and that’s absolutely fine. We take our tagline, “Your Memoir, the Way You Want It,” seriously at Modern Memoirs, and I respect a person’s wish to protect others’ privacy even as they share much about their own lives through their writing. It’s a fine line to walk. But, oh, how I love a good love story!

“The Story of the Elopement” by John A. Lennox, a print of which hung in Tazzy and Fred Lambert’s home and is now in Megan St. Marie’s office at Modern Memoirs

My Modern Memoirs office is filled with mementos from ancestors’ and relatives’ love stories, including one to which I can only tangentially lay claim as family history. My uncle Steve Lambert recently gave me a framed picture from an 1897 edition of The London News, which hung in the home of my great-grandparents Alfred “Fred” Damian Lambert (1882‒1963) and Anastasie “Tazzy” Delia Raymond (1886‒1971). Entitled “The Story of the Elopement,” this print of a painting by John A. Lennox has a great narrative quality, inviting the viewer to speculate about the story the painter was trying to tell. An older man in the painting looks upset, his posture rigid as he stares out a window with his back to the room, while a young woman sits with her head on the table in front of her, weeping. Is this an angry father and his daughter after her elopement? To me, that seems likely, but there is no accompanying text to offer the precise details of what transpired between these two characters and the others in the composition.

“The Reconciliation” by John A. Lennox

A bit of online research by staff Genealogist Liz Sonnenberg revealed a companion image called “The Reconciliation,” by the same artist, which ran in The London News soon after this first picture was published. In it, the same cast of characters is present, and the scene looks relaxed and joyous. Whatever upset the elopement caused in the first painting seems resolved in this second scene. I ended up wondering: Why did my Lambert great-grandparents keep that first print in their home? What did they make of the domestic drama it depicts? Did this scene make them reflect on their own marriage? Or others’ marriages in their family? And, did they ever see the second picture of a happy reconciliation?

A copy of the 1905 marriage license of Anastasie “Tazzy” Delia Raymond and Alfred “Fred” Damian Lambert

The wedding photo of Megan St. Marie’s paternal grandparents, Homer Raymond Lambert and Lucienne Marie Laroche Lambert, 1936

I know that Fred and Tazzy did not elope, and in fact, I know of no stories of elopement in my family history (though I have to imagine there were some). One rather humorous family story that I did hear about the beginning of a marriage concerned my Lambert grandparents. Fred and Tazzy’s son, my grandfather Homer Raymond Lambert (1908‒1974), married my grandmother Lucienne Marie Laroche (1915‒1986) on October 7, 1936. They ended up having what might be considered the exact opposite of an elopement when her parents accompanied them on their honeymoon to the mountainous area north of the St. Lawrence River in Québec. After many months of supervised courtship in their rural, Catholic, Franco American community, this was not the romantic post-nuptial getaway my grandfather, in particular, had envisioned. As those events were recounted over the years, my grandmother would say that her parents just wanted to visit relatives along the way, while my grandfather reportedly countered that they could have done so some other time—any other time.

Wedding cake toppers used by Tazzy and Fred Lambert at their 1905 wedding

Megan and Sean St. Marie cut their wedding cake, decorated with the same cake toppers used by Fred and Tazzy Lambert at their 1905 wedding, October 11, 2014

These grandparents were married for just under 38 years, until Homer died in 1974, while Fred and Tazzy’s marriage lasted for nearly 58 years until Fred’s death in February 1963. Perhaps my favorite heirlooms from a family love story are the wedding cake toppers Fred and Tazzy used at their 1905 wedding. When my husband, Sean, and I married in 2014, we used those little figurines on our cake, too. Then last summer, I brought them to a family reunion where they decorated a cake I ordered to surprise my Aunt Molly and Uncle Hank Lambert with a cake to mark their 50th wedding anniversary. Since we married later in life, Sean and I will need to live well into our 80s and 90s, respectively, to reach such a milestone in 2064, but it would be so special to use the toppers again that year. For now, they’re protected in a pretty blue box on a shelf in my office, out of reach from my small children, who are frequent after-school visitors.

Fred and Tazzy Lambert’s wedding cake toppers decorate a 50th anniversary cake for Megan St. Marie’s aunt and uncle Molly and Henry “Hank” Lambert, 2022

The strength of Uncle Hank and Aunt Molly’s marriage has always been apparent to me, and family lore seems to confirm that Fred and Tazzy were devoted to each other, as were Homer and Lucy; but the longevity of a marriage is not necessarily an indication of its happiness. There are also stories of sad marriages and divorce in my family history, as well as those of estrangement between grown siblings, and other heartaches. It’s easy for me to encourage a client like the one I mention in the first paragraph of this piece to share more about an adored spouse; the work of guiding authors in writing about ex-spouses or estranged relatives is harder. When I’ve tried to help memoir and family-history writers decide how or if to write about strained, severed, or otherwise painful family relationships, I start from a place of empathy that arises from my own experiences of witnessing or hearing the hard family stories in addition to the happy ones.

No one gets married hoping to divorce, any more than a parent looks at their children and imagines a day when they won’t be on speaking terms. While cautioning clients against any risk of libel, my rule of thumb in guiding them editorially in writing about not just the good times, but the bad, is to consider the intentions behind the words they write, as well as their intended audience. If they are in the midst of a scene like the tumult depicted in “The Story of the Elopement,” do they hope their books will promote an eventual reconciliation? If not, what do they hope to achieve by not just writing about, but publishing, their reflections on painful family dynamics? If they imagine their children and grandchildren reading their books, what do they aim for those readers to gain from difficult family stories—beyond knowledge of the fact that virtually every family has challenges of one sort or another?

Writing about one’s life, including marriages, divorces, estrangements, and reconciliations, can bring about perspective, clarity, and sometimes even healing. Ultimately, I hope that all of our clients will write and publish their stories in ways that will bring them and their readers fulfillment and pride, joy and peace—now, fifty years from now, and for generations to come.