1. Your ancestors emigrated from China to the Philippines, where you were born the last of fourteen children. As a child, what were the challenges and rewards of being part of such a large, multi-cultural family?

Elizabeth Tan Tsai: As the youngest of 14 children, I was the baby of the family—privileged to sleep with Mother for 14 years, cared for and protected by my siblings. But I had to obey them and, in case of differences in opinion, defer to theirs. Why? We were brought up with the tenet that the older protect the younger, and the younger respect and obey the older. As for my multi-cultural heritage, I grew up among Filipinos, attended public schools, and spoke our Capiceno dialect, neither understanding or speaking Chinese, nor associating with the Chinese community. The Filipinos accepted me as one of them, and I did not feel excluded from any childhood activities, nor did I feel any racial discrimination against me. I elected Philippine citizenship when I ceased to be a minor (at the age of 21 years) and freely exercised all the rights and privileges appertaining thereto. Thank God, I have never experienced racial discrimination in the U.S. either.

2. You studied law in the Philippines and worked for a firm in Manila before coming to the United States and graduating with an LL.M. from Yale Law School in 1965. You decided to remain in the United States, where you worked as a legal writer/editor at a law publishing company, a member of the California State Bar, a practicing lawyer in San Diego, a member of the Bar of the District of Columbia Court of Appeals, and a special counsel at the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission. What was one of the most rewarding events of your varied and distinguished legal career? Also, what was your experience as a woman in the legal field and in law school at that time?

Elizabeth Tan Tsai: The most rewarding event of my career was graduating with an LL.M. from Yale Law School. It opened doors of opportunity and brought me in fellowship with great lawyers imbued with the spirit of service for God, for country, and for Yale.

In law school at Yale, I took nine courses. In eight of these, I was the only female student and all the professors were white men. None of them called on me to recite even though I often raised my right hand. At that time, students were to observe silence until the professor called their name; whereupon they would rise for the Socratic method of interlocution. My ninth class was taught by Professor Ellen Ash Peters (the law school’s first tenured female professor and later the first female chief justice of the Connecticut Supreme Court). She was born in Berlin in 1930 and, when she was nine years old, fled with her family to the U.S. I will always remember how wonderful I felt when she called on me to recite, saying, “Miss Tan.”

After getting my LL.M., I received two job offers: associate attorney in a mid-size law firm in Utica, New York, which I declined; and junior editor at the Lawyers Co-operative Publishing Company in Rochester, New York, one of 10 hired in the summer of 1965 and the first of my cohort to be promoted to editor. At the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission, I was promoted to special counsel, doubling my salary in four years and supervising a diverse staff that included three white male attorneys, one white female attorney, one Black female attorney, and the Black librarian of the Division of Investment Management.

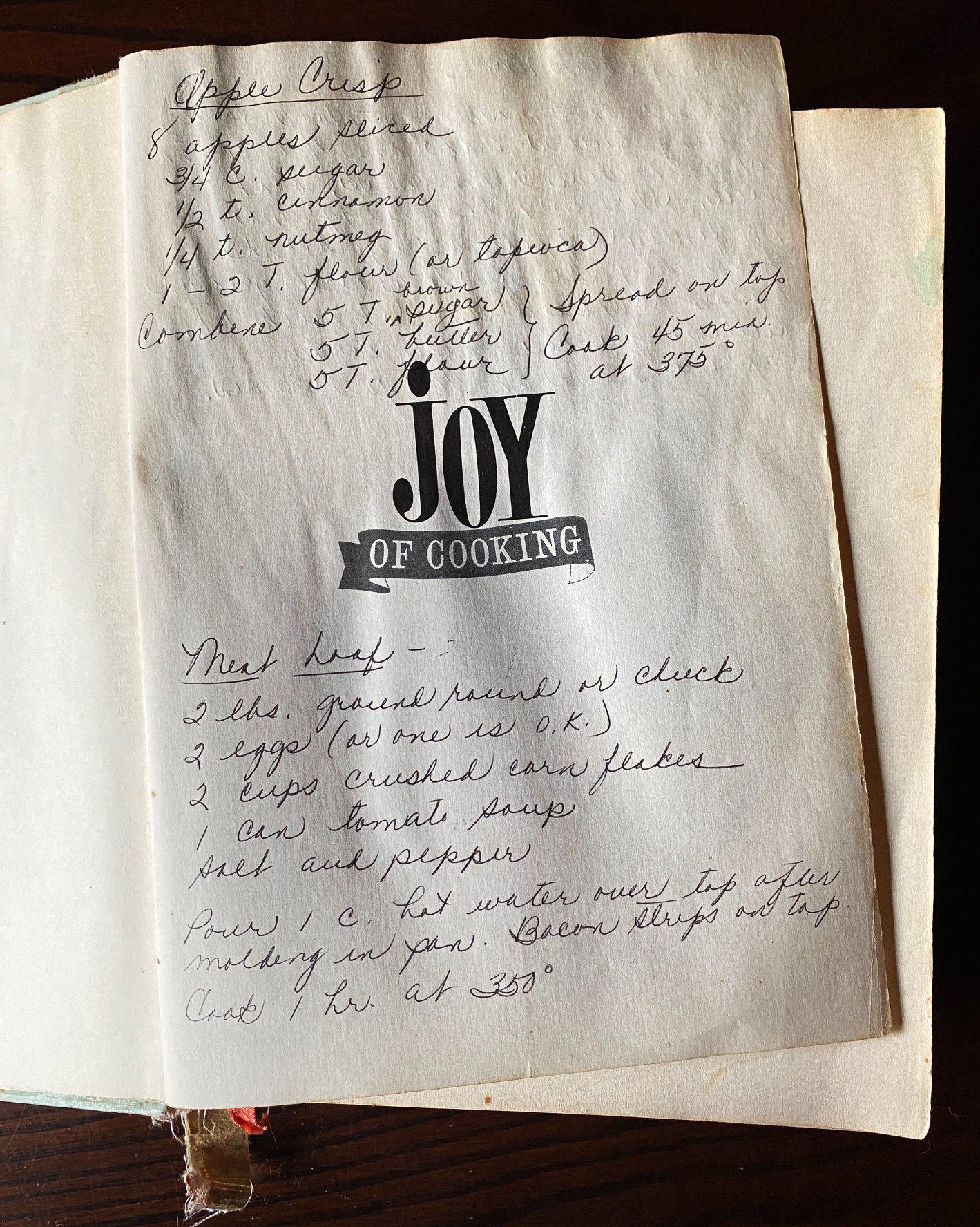

3. Your autobiography entailed translation of oral history and numerous family letters from your native language to English, and transcription of these and other materials, such as diaries, speeches, and emails. How do you feel these primary sources enhance the retrospective narrative portions of your autobiography?

Elizabeth Tan Tsai: Since these records are contemporaneous to the experiences and events described in the writers’ own words, they reflect the writers’ personality, excitement, and frustrations, while lending an immediacy to the reader. Thus, they are more vivid and factual than a pure retrospective narrative.

4. As a pastime, you love to dance. How does dancing enrich your life and inform your writing?

Elizabeth Tan Tsai: Social dancing lifts me up, makes me feel ethereal and larger than life. It is artistic self-expression and a beautiful way to know people. Greeted by smiling faces—happy to see me and dance with me—I feel one with my dance community, an extension of my sweet family; we care about each other and support one another.

My book describes the venues where I have danced and the joys of dancing there, and I see connections between my writing and dancing lives. When learning complex dances, I concentrate and keep practicing. After two hours of dance classes, I stay for the two to three hours of dance party that follows to practice what I’ve learned. Similarly, when I write, I concentrate and keep writing. Also, just as I watch dance competitions and performances to improve my dancing, I read autobiographies to craft my own, such as the one by Edward Gibbon, who wrote his autobiography when he finished writing The Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire. In fact, I got the idea of beginning each chapter with an epigram from U.S. Supreme Court Justice Sandra Day O’Connor’s Lazy B: Growing Up on a Cattle Ranch in the American Southwest.

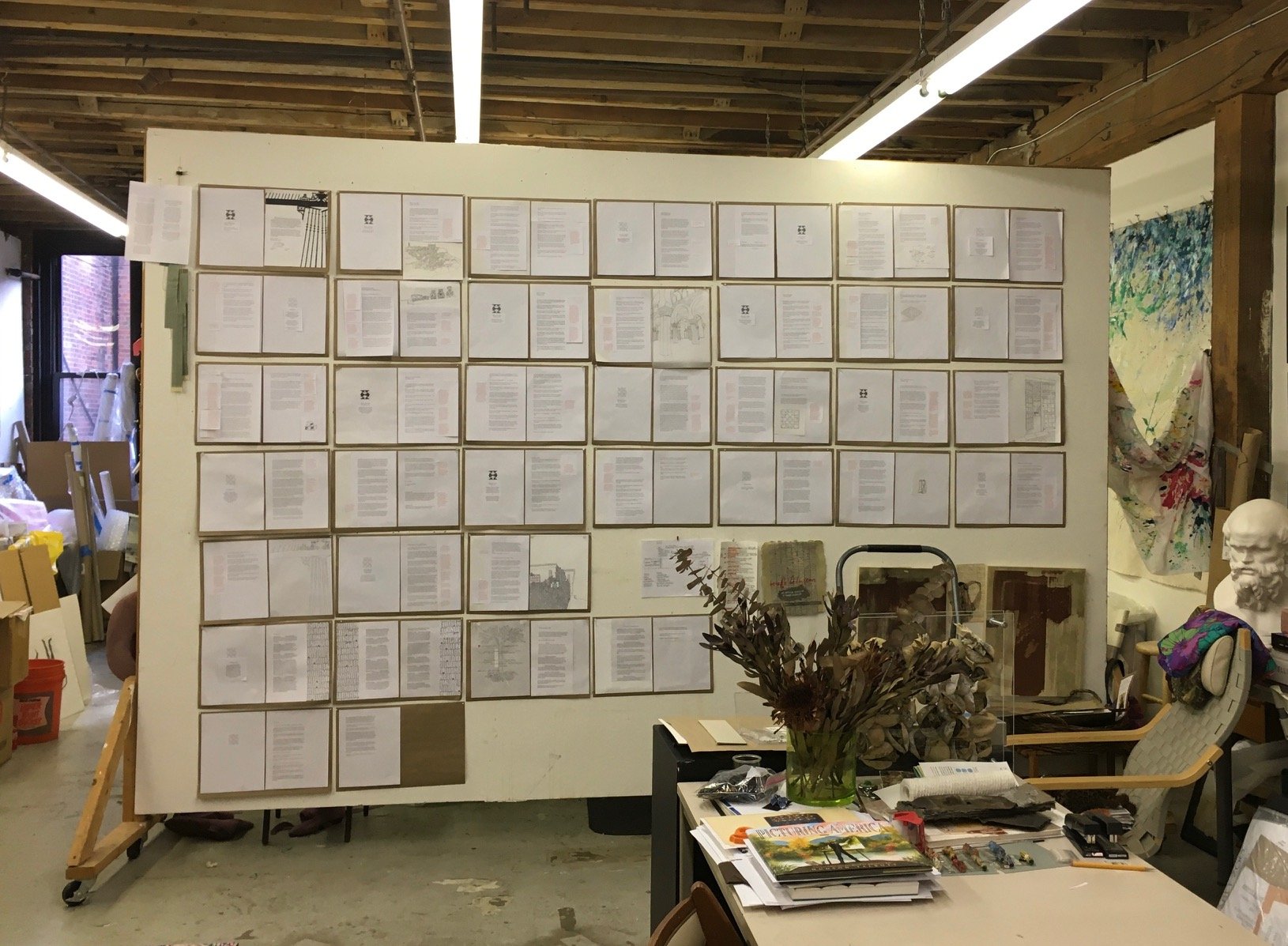

5. What was it about your first Modern Memoirs experience that convinced you to pursue your second project with us as well?

Elizabeth Tan Tsai: A Grandmother’s Diary was a way to test the waters. I thoroughly enjoyed working with Modern Memoirs, and I was confident that they would be as superb and as encouraging, if not more so, with the second project. The experience of working on the autobiography was akin to, but more fun and fruitful than, taking a course on memoir writing at a university. I learned a great deal, I had the fervent support of experts, and I exulted in the friendship of noble souls.

6. You said that you undertook the autobiography project at the behest of your two children. What were your goals in creating it? Whom do you intend your readers to be, in addition to your immediate family?

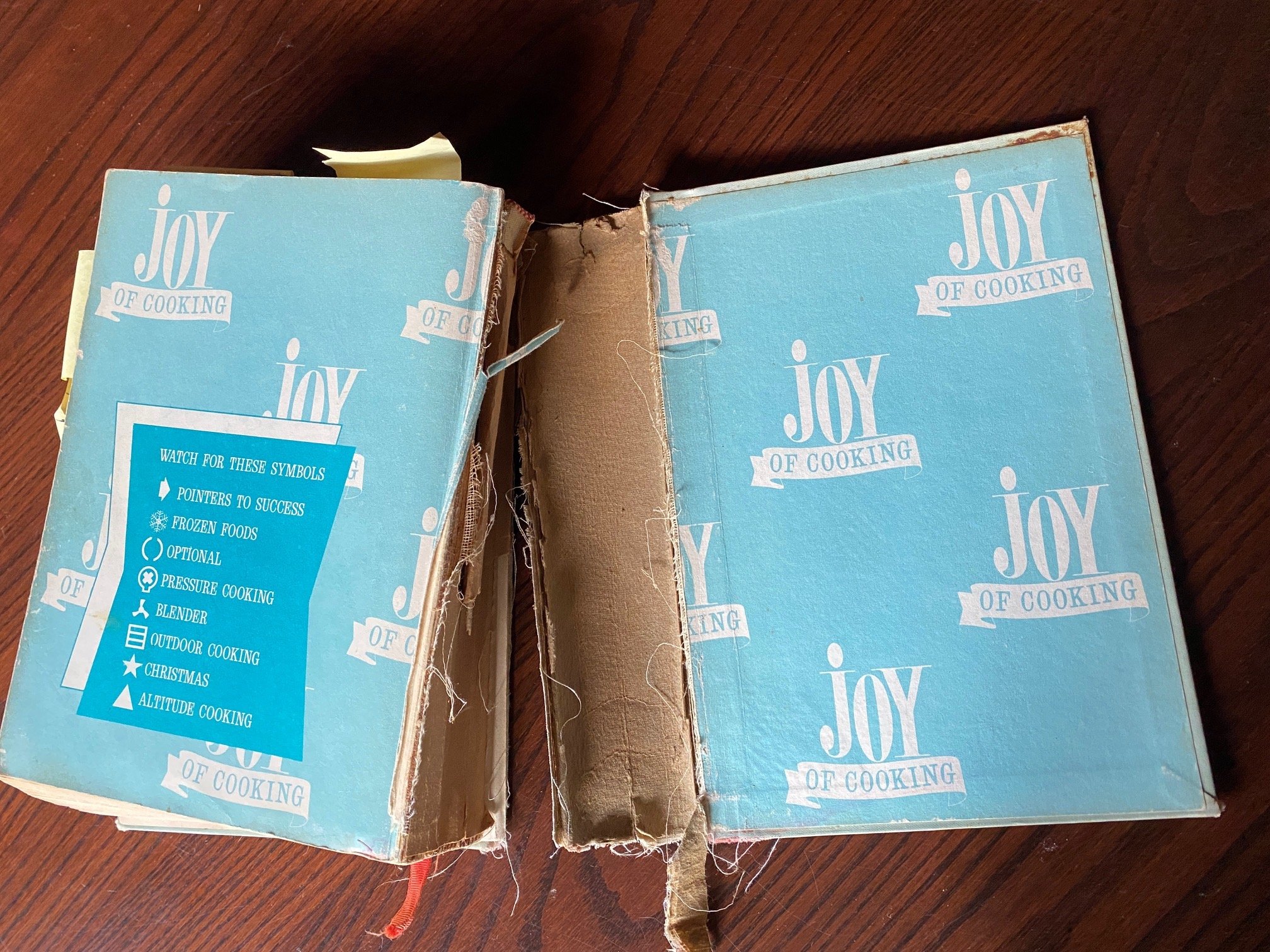

Elizabeth Tan Tsai: I wrote my book to leave—in one compendium—records of my life and family felicity. I meant it for my children and grandchildren, my siblings’ descendants, and organizations interested in preserving this family history. This book is my best piece of writing—useful and beautiful. I am happy with the finished, designed product, and have given copies to my close and extended family, Yale University’s Sterling Memorial Library, the Yale Law School Library, the Law School Alumni Reading Room, the Chinese American Museum in Washington, D.C., and the Library of Congress. I feel that, having discharged my duty to record our family history and ensure its preservation for posterity, I can die without regrets.

Though it is still early, I have already received congratulations on what readers have described as “an amazing undertaking” and “a spectacular product.” One grandniece said she is happy to learn the story of our family, and another said that it stirred her to tears. My daughter, Pearl, is also a graduate of Yale, and I included some of her letters from school in one of my volumes. A fellow resident in my retirement community, who attended Yale for eight years, said he found her letters to be “downright nostalgic,” and said, “I was really taken by Pearl’s experience with Yale’s internationalization, both in the student body and the curriculum.”

My husband has read my autobiography, as well, and said that he learned a lot about my parents, how they raised me, and how I raised our two children to be great parents, capable professionals, and good and useful citizens of a modern society. It’s wonderful to know that after 55 years of marriage, my husband is still learning about me.