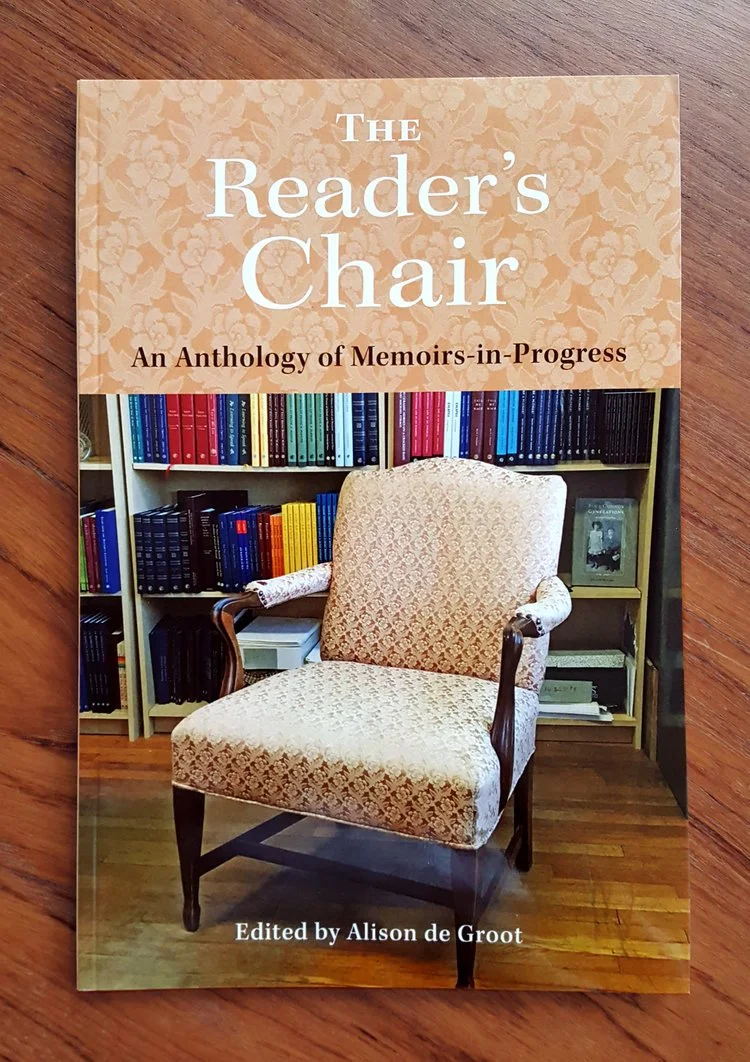

Director of Publishing Alison “Ali” de Groot began her official employment at Modern Memoirs in September 2004. In honor of her 20th anniversary this year, we are presenting a two-part blog series in which we asked de Groot to reflect on two books of her own. Last month, in Part 1, she discussed Learning to Speak, a bereavement book dedicated to her mother, which de Groot published herself in 1999. In Part 2 below, we look into The Reader’s Chair: An Anthology of Memoirs-in-Progress, edited by de Groot and published by Modern Memoirs in 2018.

In 2002 Kitty Axelson-Berry, the founder of Modern Memoirs, launched First Person! First Night!, a place for writers in the Amherst, Massachusetts area to gather on a monthly, drop-in basis. On the first night of every month, writers were invited to read aloud their works-in-progress. The group, facilitated by Ali de Groot and Linda Stenlund, had anywhere from four to ten participants and met faithfully at the Modern Memoirs office for thirteen years, until 2015.

To honor this group, Axelson-Berry and de Groot envisioned creating an anthology of pieces written by longtime members. The Reader’s Chair is an informal collection of these writings. In the book’s Introduction, de Groot describes how, to prepare for each monthly gathering, she and her co-facilitator would “set up a bunch of mismatched chairs in a tight circle and place an old flexible floor lamp next to the designated reading chair, a frayed pink upholstered affair that had belonged to Kitty’s mother.” Today, over twenty years later, the reading chair remains a cherished piece of furniture in the Modern Memoirs office.

1. How does this anthology reflect the breadth of life experiences and writing styles that memoir can encompass?

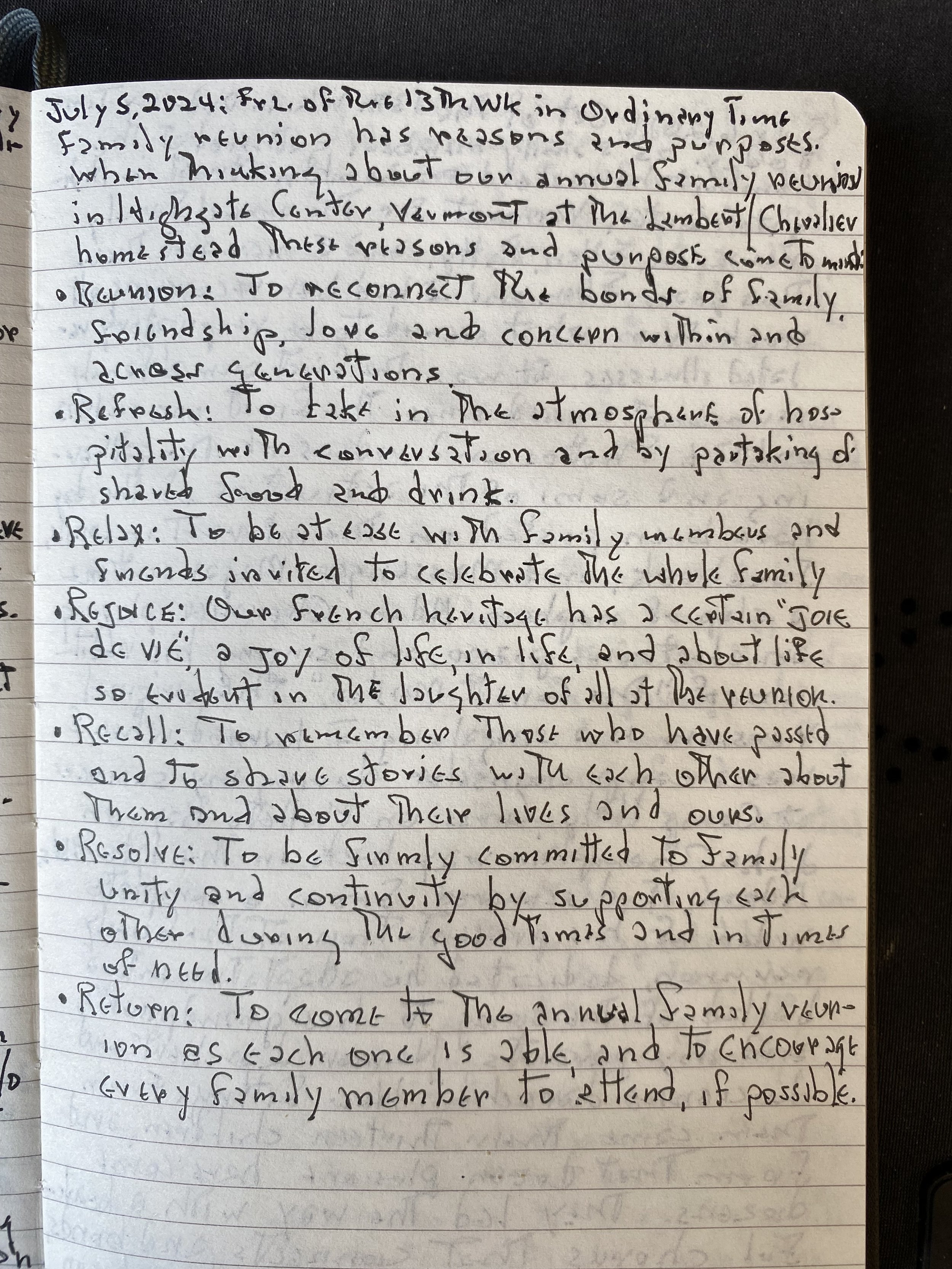

Ali de Groot: I believe memoir writing can come in all shapes and sizes. Since life is full of experiences that are impossible to fit into one style, a memoir can be anything the writer wants it to be. I’m not talking about commercial “bestseller” memoirs. I’m talking about what we focused on in our group: personal, authentic, raw writing in whatever form it might take—a story, a letter, a poem, a dream, even a to-do list.

2. On one of the first pages of the book, you include a quote by Anaïs Nin: “We write to taste life twice, in the moment and in retrospect.” How do these words convey the essence of memoir writing?

“Writing is a free journey, a window into understanding on a deeper level.”

Ali de Groot: One of my favorite writers in high school was Nin, so I had to include this well-known quote. When I read her published diaries, I realized that journal writing was really a form of memoir. As an avid journaler myself, I came to value this style of writing. For me, memoir writing is a powerful way to relive and make sense of an event after it has happened, be it positive or negative, important or inconsequential. Writing is a free journey, a window into understanding on a deeper level. And it allows me to face things I might not have wanted to face, and learn things about myself or others that I didn’t know.

3. As you describe in the Introduction: “We would devote some time after each person’s reading for constructive feedback from listeners, if desired, but ‘literary’ critique was discouraged and almost nonexistent. After all, these were usually raw and unedited pieces, sometimes read directly from a journal, a notebook, letters, even scrap paper. I think the majority of us had no intention of publishing our work (or even re-reading or revising it), although most of us were writing abundantly during those years.” What is an advantage to doing this type of writing, as opposed to working and re-working the actual chapters of a book? What is the advantage to this type of initial feedback?

Ali de Groot: Back to the journaling topic, this kind of writing is simply a way to get snapshots of the mind. It’s immediate, accessible, and you don’t have to analyze, edit, analyze, edit, etc. and drive yourself nuts trying to figure out the “best” way to say it. In my view, the “best” way doesn’t always live up to the most authentic way to say something.

The point of reading aloud wasn’t to get feedback. It was to have witnesses to a story in real time. A kind of magic happens for the reader (and the listener) in this setting. The feedback was secondary. Living in a very literary town like ours, I admit I wanted to avoid looking like a group of aspiring authors. In fact, when occasionally someone’s feedback got too scholarly, personal, inquisitive, or preachy, it was a big damper and we would have to steer the comments in a different direction. I think we just wanted motivation to write and reflect, with minimal feedback, the sort that makes you want to return the next time and helps you enjoy writing for writing’s sake.

4. Since writers in the group weren’t necessarily interested in publishing their work, how did you end up deciding to create the anthology? Can you describe the publication process?

Ali de Groot: It was Kitty (my then-boss) who initiated the concept, and I ran with it. I had one day a month to work on a personal project, so I decided to use that time to work on the anthology. First I had to solicit submissions, which was difficult because we didn’t even have an email list of people who had attended over the thirteen years! I knew a handful of people’s email addresses and contacted them. I wanted more people, but in the end I only had submissions from five. Although I gave deadlines for each step, it all naturally took longer than I thought. Kitty and I did a cursory proofread of all the pieces, but NO editing, keeping in line with our philosophy of keeping the writing raw and authentic. I designed the book, and we went to print, ordering just enough copies for each of the five members, who requested anywhere from two to twenty copies.

A bittersweet thing that happened later—there was one member, a close friend of mine, who initially didn’t even want to pick up her two copies. She had been in the group since its inception but was very humble and hesitant to let anyone know about the book. Around four years later, she became ill and passed away. We read some of her original poems at the funeral. And can you imagine what happened when people found out that she had been writing poems, stories, and journals for decades? They all wanted copies of the book. I’ve ordered reprints for her family and friends. So this book continues to honor her and proclaim to all those who knew her what a devoted writer she was. It’s a little glimpse into her soul.

5. If a writer does not have access to this type of group, what is the next best thing they can do to get themselves “writing abundantly”?

Ali de Groot: Form a group! Get a writing buddy! Even a virtual partner on Zoom! Make time to write on a regular basis (duh). Journal every day. (I don’t write every day.) Let yourself loose, and don’t think about anyone ever reading it. Explore verse, rhyme, lists, letters, minutes, shorthand, any kind of writing. Try writing in another language, writing with your opposite hand, writing in pen, pencil, marker, or on a keyboard. Look at a photo and write. Look at a painting and write. Look at what’s right in front of you and write. You’ll be surprised at what comes out.

The editor (with newly published book) sitting in the actual reader's chair at former office of Modern Memoirs, 2018

The reader’s chair, originally Kitty’s mother’s chair, as it sits in the Modern Memoirs office today, 2024

Liz Sonnenberg is genealogist for Modern Memoirs, Inc.